1997

Latin American women at the end of the century: family and work

Irma Arriagada

This brief text aims to highlight some basic

tendencies in the situation of women in relation to the

family, work and poverty as they move into the new

century. The ambivalence in the situation of women are

very noticeable, especially in the spheres of employment

and the family; central elements which define their

opportunities for participation. In all areas, the

permanent paradox between the economic and family

contributions of women, their great lack of participation

and the poor representation of their interests can be

seen. This contradiction is even more clearly seen in

relation to the serious obstacles in the way of

translating women's demands into effective State policies

which aim to improve their condition and tend towards

modifying the gender system on the cultural plane.

It is obvious that as the condition of women improves,

the space they occupy becomes devalued. For instance,

with women's participation in the work market: as some

occupations become "feminised" -that is with a

higher proportion of women than men going into them- the

income they generate becomes reduced along with the

prestige associated with holding such a job. The

differences in income have been maintained in a way

similar to the situation of five years ago, along with

the range of occupations carried out by men.That is to

say, that discrimination has been reconstructed at a

different point in the scale at the same rate as the

improvement in the position of women has upset the

balance between the sexes. The point at which inequality

is established has changed and new openings for

inequality appear in social and political participation,

in employment and social security and in the family

ambit.

The work marked offers advantages and opportunities of

freedom to women, who fought their way in here and are

now fighting to broaden this space, diminishing the

effects of discrimination and segmentation, while labour

flexibility recreates new forms of exclusion and

segregation. The family structure and organisation,

meanwhile, are not so well covered by research, but it is

feasible there would be strong negotiations given the

great changes in the lives of women and the tensions

which their double lives as worker and housekeeper impose

on their time, their physical capacities and their

quality of life. The impacts the changes in the work

sphere throw onto the family and their internal

hierarchies must not be forgotten either. There are

changes in the "knowledge" and the

"power" within the family, which have been

little studied. Although it is credible to suppose the

role of women in the family is still of crucial

importance as a bridge to the new roles and rupture with

the old norms of submission.

The significance of the forms of participation and

exclusion depend on the ambits where they are produced

and the meaning attributed by the actors, hence the

discriminations are also perceived subjectively. How do

women experience the situation of inequality and the

changes in terms of negotiation, resistance,

confrontation and also "resignation" in the

fora of employment and family?

On this front, it is important to differentiate the

situation between the old and new generations. So the

younger ones begin their negotiations from a higher

starting point? The negation of the new and subtle forms

of discrimination by the youngest generations, allied

with the growing individualism and the exaltation of an

apparent equality in the most modern systems, stand in

the way of changing the gender structures by making the

new aspects of subordination invisible in the subjective

consciousness. However, as a generation, they also have

better educational and professional opportunities and a

new outlook on the family.

The present context

Adjustment policies were applied from the outbreak of

the debt crisis, and these tended to prepare the Latin

American economies for their insertion into the new

globalised international model which was held up as the

only development alternative. As a result, the most

defining characteristics of the current situation include

increasing integration into the international, regional

and subregional market, movements of capital, information

and technological innovation.

The role of the State as defined by the new model

meant a reduction in social spending, with the consequent

repercussions for the poorer strata of the population.

Furthermore, the State was expected to have greater

intervention in the markets and develop new regulatory

functions. Thus the current Latin American State has been

gradually modifying having to face several challenges,

including assuring governability through the clear

regulation of conflicts, redefining its own functions

according to the great changes of the new international

economic order and finally, assuring the long term

stability of the economic transformations and their

acceptance on a social level.

In the field of the most recent plans and policies, we

need to stress that plans were designed for equal

opportunities and other instruments to bring in gender

policies in several Latin American nations. This process

has been largely due to the development of the women's

movements and the pressure they have exerted with their

demands in several countries. These instruments have been

the combined product of a process of consultation with

specialists and analysis of the social experience of the

women's movements (Guzmán and Ríos, 1995), both

regional and European, especially the experience

accumulated in Spain.

However, although we contributed to the creation of a

special situation to redefine functions of public

management, there are great difficulties in getting

gender policies accepted and put into action, related to

resistance to change, with a multiplicity of social and

political agents implied, depending on conflicts of

interest and the institutional diversity of each country.

The ideological resistance which has developed against

the issue from religious and political fundamentalists,

amongst other factors, are especially strong.

The recent economic trends do not offer much hope.

Even though some productive sectors have been modernised,

allowing for comparative advantages to be obtained in the

export of new goods, the generation of productive

employment has not been sufficiently dynamic to

incorporate all the population of working age. The work

markets have become increasingly segmented, the

unemployment and subemployment rates are especially high

amongst women and young people. The average regional

growth of the Gross Domestic Product for 1995 was of

barely 0.3 % and represents a fall of 1.5% of the per

capita product, in relation to the previous year. An

important achievement for the region was the reduction of

inflation in nearly all the countries, whereby the

regional rate fell from 340% in 1994 to 25% in 1995

(ECLAC, 1996a). In 1996 growth reached 3.4%, half of the

aim proposed by ECLAC (ECLAC, 1996b) as necessary to be

able to tackle poverty adequately.

Without doubt these overall results have also had

repercussions on the social budgets of the countries -

those which have not yet recovered the levels of before

the debt crisis. In the majority of countries the levels

of social spending increased in relation to 1990,

especially on education and social security, however, two

thirds of the countries show very low levels of per

capita spending in dollars: less than 100 dollars per

person per year are spent on health and education (ECLAC;

1996).

Is poverty concentrated

amongst women?

The new role of the State, the debt crisis, the

effects of the adjustment programmes and the reduction in

social spending have had long term consequences which

have been expressed in the social and gender planes, in

increasing poverty, unemployment both structural and born

of the situation, concentrated on women and young people,

and in an increase of precarious and unusual employment,

where women are found in the less well paid areas of the

productive and sub-contracted occupations. There has also

been a reduction in civil service posts which has

affected women in a discriminatory manner, as the main

users and employees of the public sector.

Poverty, with its low income and inability to satisfy

basic needs, constitutes the extreme form of the

exclusion of individuals and families from the productive

processes, social integration and access to

opportunities. It is thus one of the most perverse

consequences of a development model, whose fruits are

distributed in an inequitable manner.

From the social exclusion perspective, women in Latin

America continued to be poor for gender related reasons,

independent of the social strata they belonged to because

of their families. Their role in society robs them of the

possibility of acceding to ownership and control of the

economic, social and political resources. Their

fundamental economic resource is paid work, which they

have access to only in highly unequal conditions.

Women who live in poor homes tend to be even poorer

than their male counterparts, especially when they are

also heads of household. They must carry out domestic

labour, raise children, and care for the sick alongside

holding a paid job. All this work is carried out in poor

conditions meaning extensive working hours and therefore

a poor quality of life which results in physical and

mental exhaustion.

At present, woman-maintained households are becoming

more common due to the economic tendencies which force

women to seek their own income, like increasing poverty

and demographic and social tendencies, like migrations,

widowship, marital breakdown and teenage pregnancy

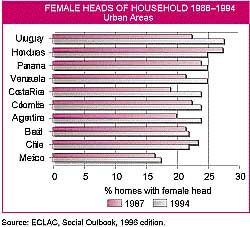

(Buvinic, 1991). Even though these data are not totally

reliable -given the definition of what constitutes a

female head of household in the censuses and surveys, and

as the statistical information is incomplete- in Latin

America at least one in five urban homes is maintained by

a woman (between 20% and 30% of the homes, and in the

Caribbean region this reaches up to 40% and beyond),

which means, in real terms, the absence of stable

partnerships. This growth was very marked in the last

decade and it is probable that the trend will be

maintained and/or increased, as long as the phenomena

that caused it are maintained (ECLAC, 1994, 1995 and

1996) (See Graphs 1 and 2).

A large amount of these homes are headed by unmarried

or separated women, most of whom are young. They are one

of the most vulnerable groups of women in the region

because they experience the greatest difficulties with

maternity. Again, within this section there is the

increasing group of adolescent mothers, who add extreme

youth and poverty to the fragility of the leadership of

the home (Buvinic and Rao Gupta, 1995). In nations with

advanced demographic transition, homes headed by widows,

especially in the urban areas, are an increasing

phenomenon which must also be adequately considered in

the design of social policies.

The traditional model of the family which is

habitually used for planning, is made up of a head of

household who is the provider, a housewife who does the

domestic work and children who -according to their

ages- are either in the educational system or the work

market until they make up new family nucleus. However,

current studies show this family model is far from

predominant. For example, in Chile, less than half of all

families are like this: 33% (Bravo and Torado, 1995), as

an increasing proportion of families have more than one

person acting as provider (ECLAC, 1995), in others, the

only provider is the woman (Valenzuela, 1995), while in

extreme cases of indigent families the children are

participating in the work market at an increasing rate

(Arriagada, 1996).

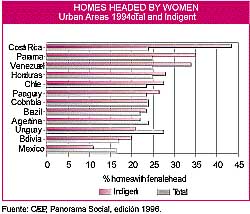

Amongst the indigent sectors, there are a greater

number of female heads of household. This sector of women

has only recently been "discovered" by the

public policies and several countries have programmes

especially directed towards them, which seek to reduce

the depth of the indigence without modifying their gender

condition and the consequences of overburdening with work

and subordination which their condition implies.

Poverty and gender biases

Although the measuring of poverty by the family income

method does not allow us to determine whether there is

greater poverty amongst women than men, it is feasible

there are gender biases in poverty if we analyse the

factors which determine it. In this way, the main factors

include: the number of contributors to the home, the

number of hours worked, unemployment, the jobs and

incomes of the members of the home. In the case of

indigent female heads of household the number of

contributors is smaller.

For 1994, it was confirmed that between 17% and 27% of

urban homes were led by women and the indigent homes

maintained an overrepresentation of women heads of

household (ECLAC, 1996) (See Graphs 1 and 2). It can also

be confirmed that there were gender biases especially in

pay per hour received by men and women, the amount of

working people per home, in the unemployment rates and in

the average number of hours worked (ECLAC, 1995).

However, for all the countries in general it cannot be

clearly proven that the situation is developing towards

an increasing feminisation of poverty, for while female

leadership of homes increased between 1980 and 1994,

there was a greater increase in the number of these

amongst the non-poor than the poor homes. Independently

of the methodological criticisms of the way of measuring

female home leadership in the surveys, the heterogeneity

of the women maintained homes this data reflects, must be

kept in view if we wish to understand the diverse living

conditions of the women along with wishing to modify

situations of extreme need and gender inequalities.

The increase in female led homes in the non-poor

sectors is due to several situations like the increasing

number of divorces and separations, where women do not

form new partnerships, and there are more unmarried women

and widows now living independently. All these situations

show new cultural patterns which increase the diversity

of family situations.

Changes in the family and the

role of women

The processes of the modernisation of the family have

not only changed its structure but also its functions.

Thus, the family concentrates on the affective functions

of caring for and socialising children, while other

functions of a more instrumental type, like education for

work, and economic production for the market, were

redirected towards other social instances. Historically,

the economic productive family functions have been losing

importance given the modifications in the productive

structure, such that there is increasing distance between

the home and production for the market.

In the present day, the market tendencies in

employment available could turn this situation round as

the new forms of sub-contracting and outworking in

certain sectors of the economy (in Chile, for example, in

the clothes making trade), have once more placed the

woman in the home, linking productive and reproductive

tasks. This strategy has a distinct character, as the

production is directed towards the market, both national

and transnational, and the result in an economic model

which tends to reduce the cost of the workforce to a

minimum.

In Latin America the family appears to have evolved

from a "Victorian" situation to a situation

where the public ambit is expanding and the private

reducing, which is in line with the modern societies,

which are more secularised and where there is greater

exaltation of equality and individualism. In this way,

the dividing lines between the public and private worlds

have become more flexible and the permanent change has

tended, in all referring to the family, towards

broadening the public space.

The more definitive functions of the family, like

reproduction and the regulation of sexuality have

diminished as families are having increasingly fewer

children (and there are an increasing number of children

born outside of marriage where their parents do not form

a family) and sexual activity is increasingly occurring

outside of marriage.

Thus many of the functions of the family which were

previously carried out within the home began to occur

outside this ambit, producing an inversion of the amount

of time people spent in their homes, and a modification

of the ways in which the family and its functions are

seen.

At the moment we are living through a process of

change in the gender system: the family roles are tending

to become more flexible - from a highly segregated model,

like the traditional one, to shared roles, where the

participation of both men and women in the work market is

no longer argued over, but the different arrangements for

caring for the children and the housework are negotiated.

The most visible point, and the main factor which

began the breakdown of the traditional model, was the

massive incorporation of women into the work market

(which will continue into the future), most of whom, up

until now, have not broken with the traditional system

and carry out a double work-day. In other groups a slow

and difficult process of negotiation has started within

the couple to develop a new model of shared

responsibilities in the home. Some studies indicate that

the tasks which present least resistance to sharing

include caring for the children, but not housework

(Sharin, 1995). Without doubt this will be one of the

aspects which differentiates the old from the new

generations.

Access to Knowledge

The situation in relation to the access to knowledge

differs widely across Latin America and it is possible to

find nations where there are high levels of education

throughout the population alongside others which have

only a minimal educational coverage and where 47% of the

women are illiterate - as is the case in Guatemala2. At

the beginning of the nineties there was a great

improvement in women's access to the various levels of

education and approximately 48% of those enrolled in

secondary education were women. This improvement will

later be reflected in the labour markets, given the high

levels of participation of women with university level

education. Advances are also being made -although on a

lesser scale- in reducing the segmentation according to

educational areas, with a marked increase in women

enrolling in habitually male lines of study in higher

education.

In this, as in other issues, a generational overview

is always useful. We are seeing a tendency in the

educational plane whereby young women are gaining a

strong foothold in the basic and medium levels of

education, where, in some countries, they are surpassing

the level achieved by males, while the adult generations

show levels of illiteracy and lower educational levels.

In several regional countries in the nineties, women form

a majority university students (Panama, Cuba, Colombia,

Uruguay and Venezuela).

Increasing female economic

participation

For Latin America as a whole the vast majority of the

jobs generated in recent years have been in the less

productive sectors: small and micro businesses and

non-professional self-employment.

The increase in female employment is found in these

groups and resoundingly outdid the growth in male

employment. Thus, between the early eighties and the mid

nineties male urban activity has been maintained at

around 78%, while female activity increased from 37% to

45%. This increase has mainly occurred amongst women aged

between 25 and 49 years-old, that is, those who are also

undertaking the reproductive tasks to a greater degree

(See Arriagada, 1994).

Economic growth has promoted the demand for female

employment in the structured areas of commerce and

services. This depends on their educational levels, and

the younger professionals have especially been inserting

themselves into the more modern areas of these sectors

with relatively high incomes, but always lower than those

offered to males with similar qualifications. The

professional work market continues to be segregated

according to gender, partly as a consequence of

segregation in education and training, and also because

of the still present cultural norms on the role of women

in society. For the majority of countries there is

greater discrimination of earnings against women the

higher they go up the educational levels. Discriminatory

practices in contracting persist (both open and hidden)

long with difficulties in access to training, promotion

and both horizontal and vertical mobility.

Despite this, an elevated proportion of women with

high educational levels participate in the labour market,

contributing with their work to the generation of goods

and services; and providing an indispensable income for

their family group, both in order to satisfy the

increasing consumer needs imposed by the economic model

and to pay for the increasingly expensive health and

education services resulting from the privatisation of

these services in the region.

Women's income in the home

As a greater number of women live alone or are heads

of household with dependants, their responsibility for

the survival of their families has increased in the last

20 years. Often, pregnant teenage girls do not get the

support of their partner, and older adults are not

supported by their male children - tendencies which

increase the burden on women. Although women live with a

partner, the male income obtained is sometimes so

insufficient that the women and children must take on the

double burden of domestic work and work outside the home

in order to supplement the family budget. A study in

Mexico found 17.1% of homes, independent of the sex of

the head of household, had an exclusively or

predominantly female income (Rubaclava, 1996).

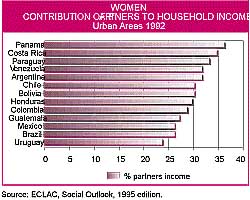

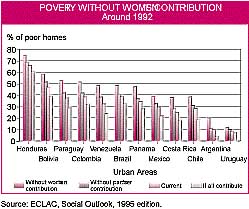

In the ECLAC "Social Outlook", 1995 a

simulation exercise established how much poverty would

increase if women did not contribute to the household.

The results were clearly decisive: without the female

income of married women, the poverty in the home would

increase by between 10% to 20% (See Graph 3). For the

group of homes in general, married women contribute

around 30% of the income with variations according to the

country. Women in 1992 contributed between 23 and 36% of

the household income, and in the indigent homes, women's

economic contributions to the budget was even higher (See

Graph 4).

Case studies show the economic income of the women of

poorer sectors -in contrast with that of the men- was

distributed in a more equitable manner between the

members of the household and was totally destined to the

consumption needs of the family (Buvinic, 1991), which

confirms the importance of women's income to their

homes.

The contribution of domestic

labour

All societies assign women the daily reproduction they

carry out through housework. This is done in an isolated

parcelled-off manner inside each home, its economic value

is not recognised and it is distributed unequally

according to the level of development of each nation,

social class, cycle of family life, geographical area.

The UNDP calculated that in the developing nations 66% of

women's work is outside the system of national accounts

(SNA) whereby it is not accounted for, recognised or

evaluated (UNDP, 1995). This greater effort by women is

expressed in a greater number of hours taken up by their

market and domestic work.

The institutional support systems to care for children

and old people are practically non-existent. The

nurseries and pre-school services have a low coverage,

especially for those who most need them: the poorest

women who work outside their homes. In the same way,

caring for old people and invalids also falls back on the

families, that is, on women, as there are very few

support mechanisms, and these are very costly because

they are private. In Latin America, pre-school coverage

for children aged 0 to 5 years-old reached 7.8% in 1980

and doubled to 16.8% in 1991. In the majority of cases it

was concentrated in the private sector and in urban

areas. In some cases the amount of coverage has been

increased and in others there have been legislative

attempts to make pre-school education obligatory.

However, in the majority of regional nations there is

still a lot to be achieved on these fronts. The concern

for the older population is still less explicit, despite

the fact that in several regional nations the older

population is becoming an increasingly important

proportion of the population.

We need not only to broaden the support social

institutions can offer to the family but must also modify

the participation of the other members of the home within

this, so as to better balance the gender roles in social

reproduction.

In conclusion, the cultural changes related to

modifying perceptions of the functions and structures of

the family and their interrelations with the economy,

along with modifications to the gender structures are

still a pending task for the 21st century. It is to be

hoped the contributions and needs of men and women will

be better balanced in the new century, modifying their

roles in the social and political ambits as well as in

the employment and family areas in a positive manner. The

organisational and planning capacity of women could be

the keystone of accelerating this process.

Bibliography

Arriagada, Irma (1996), "Infancia trabajadora y

políticas: una prioridad social", Presentation at

the IV Meeting of the LatinAmerican Inter-Parliamentary

Commission on Human Rights, Concepción, Chile May 31 to

June 1, 1996.

(1994), "Transformaciones del trabajo feminino

urbano", in Revista de la CEPAL No. 53, Santiago de

Chile, August.

Bravo Rosa and Todaro Rosalba (1995), "Las

familias en Chile: una perspectiva económica de

género" in Proposiciones 20 (Aproximaciones a la

Familia), Ediciones SUR, Santiago de Chile.

Buvinic, Mayra and Geeta Rao Gupta (1995),

"Women-Headed Households and Woman. Maintained

Families: Are They Worth Targeting to Reduce Poverty in

Developing Countries?" in Economic Development and

Cultural Change, edited by the International Centre for

Research on Women (ICRW), Washington, U.S.A.

Buvinic, Mayra (1991), "La vulnerabilidad de los

hogares de jefatura femenina: preguntas y opciones de

política para América Latina y el Caribe" CEPAL

Serie Mujer y Desarrollo, Santiago, Chile.

Economic Commission for Latin America and the

Caribbean (ECLAC/CEPAL) (1996) Panorama Social de

América Latina Edición 1996, (LC/G. 1946-P), in print,

Santiago, Chile.

(1996a) Panorama Económico de América Latina 1996,

(LC/G. 1937-P), Santiago, Chile, September.

(1996b) Fortalecer el desarrollo, Interacciones entre

macro y microeconomía, (LC/G: 1898 (SES26/3), March.

(1995) Panorama Social de América Latina Edición

1995, (LC/G. 1886-P), Santiago, Chile.

(1994) Panorama Social de América Latina Edición

1994, (LC/G. 1844), Santiago, Chile.

Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO)

e Institutivo de la Mujer de España (1995), Mujeres

Latinoamericanas en cifras, Tomo Comparativo, Santiago,

Chile.

Guzmán, Virginia y Marcel Ríos (1995), La dimensión

de género en el quehacer del Estado, CEM, Ediciones CEM,

Santiago, Chile, October.

Jelín, Elizabeth (1994), "Las relaciones

intrafamiliares en América Latina", in ECLAC/CEPAL

(1994) Familia y Futuro: Un programa regional en América

Latina y el Caribe, Santiago, Chile.

Ruvalcaba, Rosa María (1996), "Hogares con

primacía de ingreso femenino" in Hogares, familias:

desigualdad, conflicto, redes solidarias y parentales,

edited by the Sociedad Mexicana de Demografía (SOMEDE),

Mexico.

Sharim, Daniela (1995), "Responsibilidades

familiares compartidas: Sistematización y

análisis", in Documentos de Trabajo No. 41,

produced by the Departamento de Estudios Area Familia of

the Servicio Nacional de la Mujer (SERNAM), Santiago,

Chile.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP/PNUD)

(1995) Informe sobre Desarrollo Humano 1995, Mexico.

Valenzuela, María Elena (1995), "Hogares con

jefatura femenina: una realidad invisible", in

Proposiciones 20, Aproximaciones a la Familia, Ediciones

Sur, Santiago, Chile."

Notes

1 The opinions in this article are entirely the

responsibility of the author and do not involve the

institution she works for. She would like to thank Rosa

Bravo for her substantial contribution to this document

and Lorena Godoy for her pertinent criticism, on the

understanding that any deficiencies which exist can be

attributed to the author.

2 Cuba, Uruguay, Argentina, Colombia, Panama and

others have a female population with high levels of

education, while Haiti, Honduras, El Salvador and

Nicaragua show high levels of female illiteracy according

to data from FLACSO (1995).

|